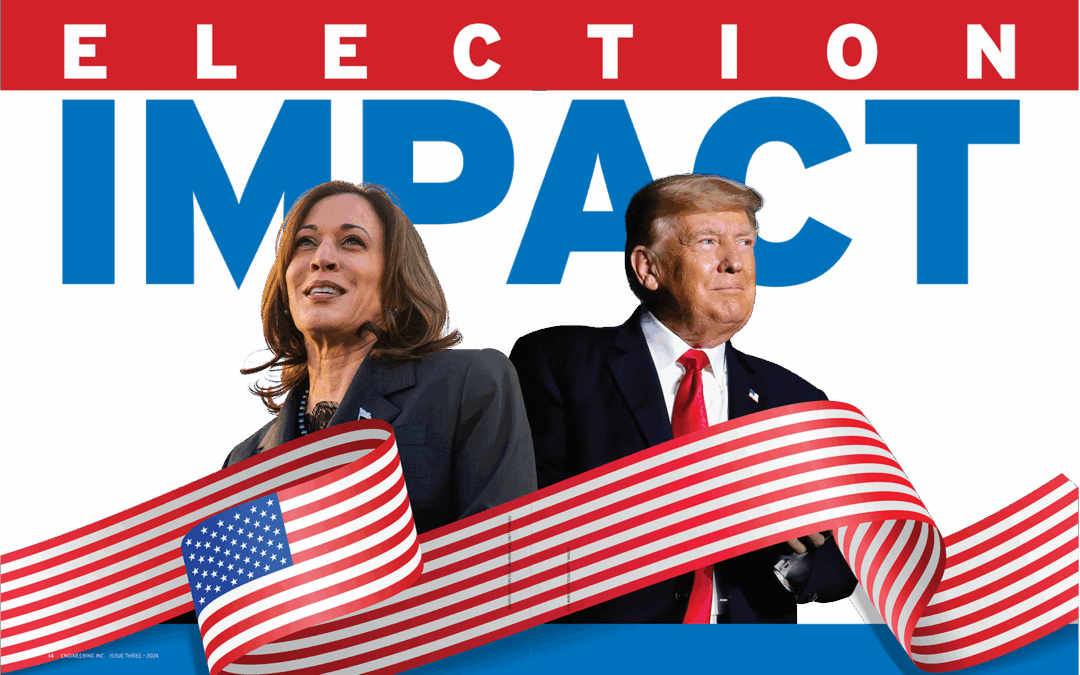

Election Impact

From taxes to energy, Kamala Harris and Donald Trump offer vastly different visions for America’s future. Here’s where they stand on the issues that most affect engineers.

The 2024 election will either put Donald Trump back in the White House or see the U.S. elect its

first female president in Kamala Harris. Either way, the margin of victory is likely to be razor-thin. Polls

conducted just after President Joe Biden announced he would no longer seek a second term suggest the

election could be decided by voters in a handful of swing states: Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada,

Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin.

The election could have a major impact on the engineering industry. Harris and Trump are likely to take

divergent approaches on key issues affecting engineers. Here’s how the two candidates may approach those

issues, including tax policy, global trade, energy, infrastructure, and immigration, according to a bipartisan

group of election and policy experts.

Taxes

In 2017, the Trump Administration championed a series of tax

cuts for individuals and corporations that The Wall Street Journal

called “the most far-reaching overhaul of the U.S. tax system in

decades.” But in 2025, those tax cuts for individuals—which

include owners of many engineering firms—will expire. That

means the president for the next four years will have to either push

Congress to keep the cuts in place or allow taxes to rise.

“Trump will not want his signature law to expire at all and has

proposed cutting rates even more,” says Rodney Davis, a Repub-

lican who represented Illinois’ 13th district in Congress for a

decade and who serves as head of government affairs at the U.S.

Chamber of Commerce. On the other hand, Davis believes Harris may let the Trump tax cuts expire.

While Trump says he’ll either keep the corporate tax rate at 21 percent or lower it to 20 percent, Harris publicly supports

raising the corporate tax rate from 21 percent to 28 percent. Her campaign also told Politico in July that she would not raise taxes on individuals making less than $400,000 per year.

“That touches our industry in terms of our members who operate passthrough firms,” says Steve Hall, executive vice president at ACEC. “S corps, partnerships, and LLCs are taxed on the personal rates. But an even bigger issue for those firms is the Section 199A 20 percent tax deduction for passthrough businesses. That expires along with the personal income tax cuts next year.”

Both of them are

protectionists. They both

are not afraid to use the

hammer of tariffs to get

their way.

HEAD OF GOVERNMENT AFFAIRS

U.S. CHAMBER OF COMMERCE

REPUBLICAN AND FORMER

CONGRESSIONAL REPRESENTATIVE

ILLINOIS’ 13TH DISTRICT

Infrastructure

One of the signature pieces of legislation from the Biden-Harris Administration was the 2021 Infrastructure Investment

and Jobs Act (IIJA), a $1.3 trillion bipartisan package that has funded improvements to the nation’s roads, bridges, and water systems, as well as hundreds of other projects. The IIJA will continue to be overseen by whomever wins the White House until it expires on September 30, 2026.

While the funding distributed to the states through established formulas has flowed fairly efficiently, an analysis by the nonpartisan Brookings Institution recently found that 80 percent of the bill’s “competitive funding” from its discretionary

grant programs has yet to be awarded.

“Trump and Congressional

Republicans might prefer to see individual surface transportation, aviation, and water bills instead of one large funding package.”

STEVE HALL

EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT

ACEC

“I think that’s going to be among the most important things for engineers,” says Cheri Bustos, a Democrat who spent a

decade serving Illinois’ 17th Congressional district and is now a partner at Mercury, a public strategy firm. Bustos credits the Biden-Harris Administration for getting that bill and the $52.7 billion CHIPS and Science Act, which provides subsidies to semiconductor manufacturing facilities in the U.S., through a highly divided Congress. And she says her hope is that a Harris presidency might include enactment of a second large-scale infrastructure bill after the current one expires.

While Trump is likely to follow through on the IIJA’s funding until it expires, at that point, “Trump and Congressional Republicans might prefer to see individual surface transportation, aviation, and water bills instead of one large funding package,” Hall says.

Davis adds that Trump would likely also focus on regulatory reforms that can help accelerate infrastructure investment. “A Trump Administration’s infrastructure plan is going to focus on permitting reforms and flexibility and simplicity,” he predicts.

Energy

On energy policy, Davis says, “I’m not sure the two candidates have anything in common.”

The chasm between Harris and Trump on energy is partly a philosophical one. Experts say Trump’s emphasis is on

boosting domestic energy production, while the Biden-Harris Administration’s energy policies have been primarily seen

through the lens of climate change. Even before she was elected as vice president, Harris advocated for policies aimed at helping poor and minority communities that she believed had been disproportionately affected by pollution.

That environment-minded approach, as Bustos sees it, has and would continue to produce new jobs under a Harris presidency. “If we can get wind and solar and even nuclear in a better place, which a Harris Administration would do, it’s going to be better for the planet,” she says. “And it still creates a lot of jobs. It’s a major investment that requires governmental help to get it in all the right places.”

To provide some of that help, the Biden-Harris Administration leveraged $375 billion that was set aside for climate initiatives in the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (a bill for which Harris cast the tie-breaking vote in the Senate). The money has been used to increase production of electric vehicles (EVs), among other green technologies.

If we see high gas

prices in the months

leading up to the

election, you would think

that would be better for

Trump than for Harris.

KYLE KONDIK

ELECTIONS ANALYST

CENTER FOR POLITICS AT THE

UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA

Trump could take a much different approach—seeking to boost domestic oil

production through increased drilling incentives and tax cuts for oil, gas, and coal firms. “A Harris Administration is going

to continue to push to restrict our baseload-generating fuels like coal and natural gas,” Davis says. “That’s going to raise

energy rates and lessen reliability in the long term. A second Trump Administration will try to push back against some of

those mandates that have been put forth by the Biden-Harris Administration already.”

To that end, Trump has suggested that he would eliminate the emissions limits on cars and trucks that Biden had proposed. If those limits are put into effect, 35 percent of the new vehicles sold in the U.S. by 2032 will need to be electric.

Whatever voters may think of the candidates’ overall divergent takes on energy, they’re likely to pay attention to one specific metric as Election Day approaches: gas prices. Kyle Kondik, elections analyst at the Center for Politics at the University of Virginia, says that the high gas prices that have come and gone under the Biden-Harris Administration hurt Biden, and that “if we see high gas prices in the months leading up to the election, you would think that would be better for Trump than for Harris.”

Global Trade

While the candidates may take very different approaches to energy, they have some surprising similarities on global trade. “Both of them are protectionists,” Davis says. “They both are not afraid to use the hammer of tariffs to get their way.”

Trump certainly proved that during his presidency. He imposed more new tariffs on imports than any president had

in almost 100 years, according to The Economist. And Trump now promises more of the same, should he return to the

White House. He has backed something he calls the “Trump Reciprocal Trade Act,” which would give him, as president,

broad leeway to impose tariffs on any country that imposes levies against U.S. goods. He also has floated the idea that tariffs might replace at least some—if not all—personal income taxes. And he has proposed a 10 percent tariff on all goods coming into the country. Plus, Trump has suggested both a 60 percent tariff and a 100 percent tariff on all imports from China.

If we can get wind and

solar and even nuclear

in a better place, which

a Harris Administration

would do, it’s going

to be better for the

planet. And it still

creates a lot of jobs.

CHERI BUSTOS

PARTNER

MERCURY

DEMOCRAT AND FORMER CONGRESSIONAL

REPRESENTATIVE

ILLINOIS’ 17TH DISTRICT

On China, the candidates have common ground. During his presidency, Trump slapped a 27.5 percent tariff on all vehicles from China and upped tariffs on a range of other products. The Biden-Harris Administration left many of those tariffs in place and in May announced even higher tariffs on an array of products from China—25 percent on steel and aluminum, 50 percent on semiconductors and solar panels, and 100 percent on EVs. That levy on EVs is four times higher than the Chinese EV tariff under President Trump—a move designed to protect the burgeoning EV industry in the U.S., which is growing in part because of tax subsidies.

“We have an EV battery plant that’s under construction in my home state of Illinois that’s more than a $2 billion investment,” Bustos says. “These are major investments, major job creators,major construction projects. The tough talk on China is popular, but we also need to make sure we get these major investments in job creation and a future EV world right.”

Harris has indicated support for an economic cooperation agreement called the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for

Prosperity that the Biden-Harris Administration developed with 13 other countries in the region. Trump, however, has promised that he would “knock out” that deal if he returns to office.

Workforce and Immigration

Trump and Harris agree that the U.S. immigration system needs to change. But they have vastly divergent ideas of what that change should look like.

Trump has proposed multiple methods for deterring migrants from coming to the U.S. and for pushing out those who enter illegally. He has said he’d renew his ban on immigration from some predominantly Muslim countries, as well as end birthright citizenship. Trump has also called for a mass deportation of immigrants who have entered the country without permission—including those who have lived in the U.S. for long periods of time.

The differences between the candidates on immigration extend to highly skilled immigrants, including those who apply

for H-1B visas. Many business groups, ACEC included, have pushed to expand the number of H-1B visas granted annually.

They’re now capped at 65,000 per year for new workers, with an additional 20,000 H-1B visas granted to people who obtain a graduate degree from a U.S. university. ACEC and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, among other groups, have argued that’s far too low a number. In 2024, almost 480,000 people entered the lottery for the 85,000 available visas. But expanding the number of visas has proved vexing for lawmakers in Congress. “It’s always been tethered to this larger debate over border security and some of the more controversial elements of immigration reform,” Hall says.

The Trump Administration enacted a handful of H-1B visa restrictions, at least one of which has been maintained under the Biden-Harris Administration. Trump has also backed off a bit on the harsh rhetoric he has lobbed at the H-1B visa program in the past. Before the 2016 election, he called the program “very bad” and “unfair” to U.S. workers. Harris has expressed support for the H-1B visa program and in 2019 proposed eliminating the per-country ceiling on green cards for permanent residents.

On visas and immigration, much like on energy and trade and,infrastructure and taxes, Harris and Trump have some deep differences. But in assessing them head-to-head, ACEC’s Hall cautions that what they may say on the stump could end up being different from what they do once in the White House. “I think you have to take some of the rhetoric with a grain of salt,” Hall says. “We are in an election season, and what we hear in that context now and what actually gets implemented in the policy next year may be two different things.”